©alvarez – iStockphoto

©alvarez – iStockphoto

The COVID-19 crisis from the perspective of

the younger generation

ed* Nr. 02/2020 – Chapter 4

The International Labour Organization (ILO) warns of a ‘lockdown generation’. Behind this lies the concern that youth unemployment could be even more serious as a result of the coronavirus crisis than it was after the financial crisis of 2008. At that time there was already talk of a ‘lost generation’.

Even before COVID-19, young people aged 15-24 were around three times more likely to be unemployed than those over 25.1 According to the ILO, one in six young people between 18 and 29 years of age (17.4 per cent) have stopped working since the outbreak of the coronavirus crisis. For those remaining in employment, the hours worked have dropped by 23 per cent2 In addition, four out of ten young people worldwide work in sectors that are particularly affected by the crisis, such as tourism or retail.3 Dismissals are more likely to occur than for older employees because of the often lower protection against termination. The chances of finding a new job in the collapsed labour market are lower than for people with work experience. And training places are also harder to find in times of crisis.

Measures and policy recommendations

International organisations such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the ILO recommend that companies provide economic incentives for the recruitment of young workers and invest in vocational training.4 Most of the government measures taken so far have benefited those, who have retained their jobs. Targeting and profiling strategies to reach the young people most affected could help to counteract the feared development. It could also be helpful to invest in economic sectors and related employment services suitable for young job-seekers.5

At European level, the European Commission has launched the ‘Youth Employment Support: a bridge to jobs for the next generation’ initiative. This includes a Council recommendation to strengthen the ‘Youth Guarantee’ and extend its scope to vulnerable young people throughout the EU aged 15-29.

In addition, the European Alliance for Apprenticeships (EAfA) has increased the number of vocational training opportunities available for young people to more than 900,000. The EAfA brings together governments and key stakeholders with the aim of improving the quality, range and attractiveness of apprenticeship training in Europe and at the same time, promoting the mobility of apprentices. In addition, short-term employment and business start-up incentives and, in the medium term, capacity building, the creation of networks of young entrepreneurs and cross-enterprise training centres should help promote the employment of young people.

The European Commission is encouraging Member States to invest at least 22 billion euros, mainly from the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), in youth employment under the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027 (MFF). Until its entry into force, funds are available from the increase in EU cohesion programmes (2014-2020). These have been topped up by 55 billion euros through the REACT-EU initiative to help bridge the gap between the initial crisis measures and longer-term recovery (reconstruction and redevelopment).

For their part, some European countries have already taken measures for training and entry into the labour market. Where measures have been taken to promote career entry, they range from subsidies to companies to the promotion of quality internships and the waiving of social security contributions for employers. In France, for example, as part of the ‘1 jeune, 1 solution’ programme, grants are given to companies to recruit trainees. For trainees under 18 years of age, the subsidy is 5,000 euros and for trainees over 18 years it is 8,000 euros.6 Young people without qualifications are offered new qualification courses. France is also planning to create 16,000 apprenticeships in the healthcare sector to double the training capacity of carers and nurses over the next five years. The programme has a budget of 6.5 billion euros.

With the ‘Kickstart’ scheme, Great Britain aims to create 30,000 new training positions and also offers companies subsidies according to age from 1 August 2020 to 31 January 2021 of 1,500 to 2,000 British pounds (approximately 1,600 to 2,200 euros) for each newly recruited trainee. In addition, hundreds of thousands of high quality 6-month internships will be created for people aged 16-24 years receiving social benefits. A fund of two billion pounds is earmarked for ‘Kickstart’.7

With the ‘Securing training positions’ Federal scheme, Germany aims to supplement existing funding instruments. Companies that maintain or expand their training level should receive training grants. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that take on trainees from other SMEs that have become insolvent due to the pandemic will receive a take-over premium. The possibility of temporarily continuing with the training in inter-company vocational training centres should be promoted. Austria also wants to significantly increase the number of places in inter-company vocational training from autumn onwards so that all young people have a chance of finding a training position.

Lessons learnt?

The ILO fears that young people are not only currently disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 crisis but that this will also have consequences for their future professional life. This can have negative effects on employment prospects, income and pensions.8

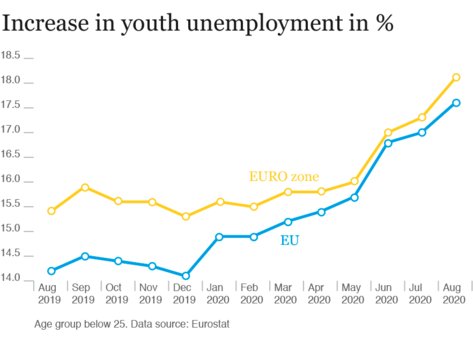

It remains to be seen whether it will be possible to effectively counter the looming rise in youth unemployment and all its consequences. Even after the financial crisis of 2008, it rose to a record high of 24.4 per cent by 2013 and despite measures such as the Youth Guarantee, it took another six years until it fell back to 14.9 per cent at the end of 2019. However, it was still twice as high as the EU average general unemployment rate. In view of the high level of sovereign debt, not all countries will have sufficient resources to counter youth unemployment. EU funds could help here.

Another question is whether the precarious situation of many young people can be sustainably remedied in the long term. Atypical employment forms such as platform work, with all the advantages and disadvantages of flexibility are increasingly common among young people. The European Commission has announced a study specifically on the access of young people to social security. The requirements for various social security benefits in different forms of employment should be recorded. In particular, the study will support the exchange of best practices.