©pressmaster - stock.adobe.com

©pressmaster - stock.adobe.com

People with disabilities

in the COVID-19 crisis

Intro

ed* Nr. 02/2020 – Chapter 5

Social isolation, difficult access to social services and care, a lack of accessible information and a higher risk of developing more severe cases of COVID-19 are a few examples that show that people with disabilities are particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to social and health impacts, the economic consequences are also disproportionately high. Experts fear that people with disabilities are at higher risk of losing their jobs. In Germany, the number of severely disabled people registered as unemployed with the Federal Employment Agency, for example, rose from 157,523 in March to 175,188 in July 2020. This was 20,638 more people than in the same month last year (July 2019).1

Because of the difficulty of finding a job in the mainstream labour market, those affected are often left with only a job from the informal sector. This excludes them from contributory social insurance schemes and, in times of coronavirus, often from state aid measures designed to compensate for loss of income. For those, who are employed, the lack of equipment or personnel support available at the workplace may make it difficult to work from the home office, further increasing the risk of job and income loss. Those, who worked in workshops have been affected by the closures of the facilities. This has had a negative impact on their pay, which is often dependent on the income generated by the workshops. Ultimately, against the background of higher expenditure, for example for barrier-free housing, aids and necessary services, even the indirect impact of COVID-19 measures increases the risk of poverty for people with disabilities, in particular when the income of family members and thus, the total income of the household, decreases.

Measures and policy recommendations

A number of international organisations have called for the involvement of people with disabilities in the response to the crisis. In May 2020, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres, called on governments to put people with disabilities at the centre of measures to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. On 18 May 2020, 138 countries, including the EU and its Member States, signed a common declaration for an inclusive response to COVID-19 that takes into consideration people with disabilities.

The ILO is calling for people with disabilities to be included in all stages of the response to the pandemic.2 In addition to immediate assistance, such as maintaining personal support and participation in the workplace, this involves, in particular participation in planning, the allocation of financial resources and employment promotion programmes, as well as ensuring inclusive labour markets and adequate social security that supports employment and economic independence. Benefits are often based on the assumption of ‘incapacity to work’, which reinforces prejudice and creates disincentives to seek work. Measures in response to the crisis should not perpetuate these misplaced incentives.

The European Parliament, in its resolution on the new EU strategy for people with disabilities after 2020, also called for the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic to be taken into account.3 The measures taken by the Member States should be analysed and reviewed for gaps. It had already previously called for the inclusion of people with disabilities in all income protection measures.4

The first measures taken by Member States in response to the pandemic were short-term assistance packages. A one-off payment of 70 million euros has been made to the integration offices in Germany for workshops, where people with disabilities work to compensate for lost earnings. For the months from June to August 2020, an “interim aid for small and medium-sized enterprises that have had to cease business operations completely, or to a significant extent, during the course of the coronavirus crisis” scheme was launched. This scheme will also benefit inclusive companies. For the months from April to June, Austria has temporarily increased the job security subsidy granted to employed people with disabilities by up to 50 per cent. The self-employed were given the existing bridging allowance of 267 euros per month, which can be granted, in the event of a disability-related need, even without providing proof.

Lessons learnt?

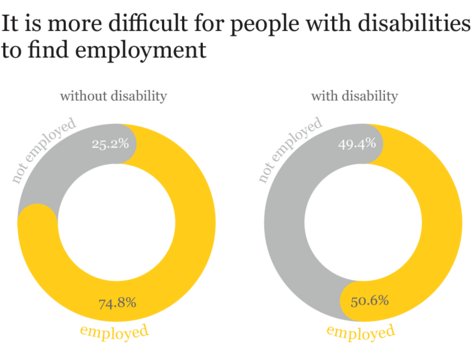

Even before the crisis, it was more difficult for people with disabilities to find employment with appropriate conditions and adequate pay. In the EU, only 50.6 per cent of people with disabilities are employed, compared to 74.8 per cent of people without disabilities.6

The European Parliament is calling for an ambitious post-2020 EU strategy with clear and measurable targets, including a list of planned actions with a clear time frame and resources, among others, in the areas of participation, independent living, employment and training. Member States are also being called upon to develop and better implement measures to promote the participation of people with disabilities in the labour market. Those, who work in sheltered workshops should be recognised as workers within the meaning of the law and it should be ensured that they are entitled to the same social security benefits as other workers.

It is still too early to assess whether measures taken, or to be taken, actually take account of the experts’ recommendations, in other words, reduce the risk of poverty faced by people with disabilities and contribute to a more inclusive labour market. The policy recommendations on employment and social security for people with disabilities, however, are largely ‘already known ones’. Despite all the technical progress and political demands, statistics on the creation of inclusive labour markets have hardly changed in the last 20 years. Only about 50 per cent of job seekers with disabilities get a job. Measures with measurable targets and a clear time frame, as proposed by the European Parliament could help reduce the gap between policy recommendations and reality.7