iStock/Galeanu Mihai

iStock/Galeanu Mihai

Different data infrastructures

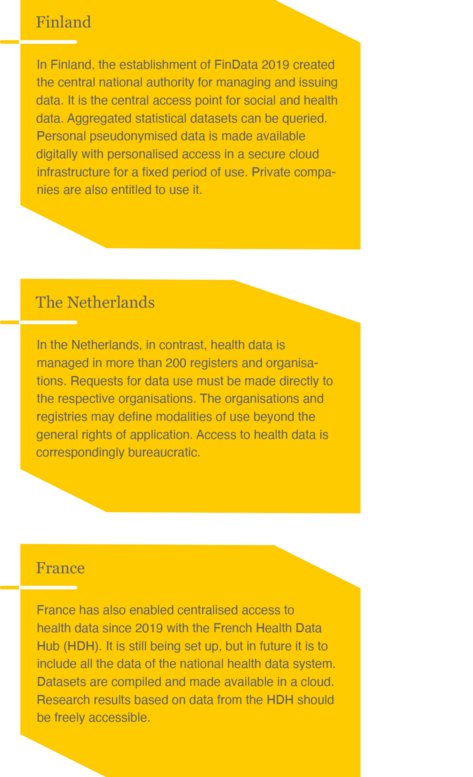

For cross-border data exchange, the existing national infrastructures must be linked via the European data infrastructure HealthData@EU. But these structures differ in the Member States, sometimes considerably.

ed* Nr. 02/2022 – Chapter 6

This concerns, among other things, data quality and formats as well as official responsibilities. In addition to the GDPR, various national regulations on health and research data must also be observed from a legal perspective. In Germany, these include regulations on social data protection under SGB V (Fünftes Sozialgesetzbuch) or the data protection regulations in the state hospital laws.

Unlike in Finland or France, German social insurance data is held decentralised. It is also specified who may use the data. There is only a small circle of users. Commercial use is not intended.

In the area of statutory health insurance, personal data such as age, gender, place of residence, as well as all cost and benefit data are compiled for each insured person. The National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds (GKV-Spitzenverband) acts as a data collection point and transmits the data in pseudonymised form to the Health Research Data Centre (FDZ Gesundheit) at the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM). The FDZ Gesundheit compiles datasets that are made available to authorised users upon request. In addition, the Federal Joint Committee makes the data from quality assurance in hospitals available for research purposes.

The datasets of the statutory pension insurance are fed by the data of the statistical reporting system. The pension insurance institutions jointly maintain a data centre at the German Federal Pension Insurance Association (Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund – DRV Bund). The social data – mainly on salaries, pensions, rehabilitation benefits – are stored according to strict conditions under the supervision of the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Access to health-related data is limited to case-by-case processing. The Research Data Centre for Pension Insurance (FDZ-RV) is an institution of the DRV Bund and has been providing information to science and research since 2004 Microdata records are made available in anonymised form according to transparent and standardised rules. These are relevant for science, since the datasets refer to the totality of all insured persons and are of high informative value. They also enable differentiated findings for questions that only relate to small groups of people.

The SGB VII (Siebtes Sozialgesetzbuch) describes the framework for social data in the area of statutory accident insurance. The accident insurance institutions may collect and store the social data necessary for the fulfilment of their statutory tasks.

Health data in the narrower sense, this is mainly data on insured persons, benefits and invoicing as well as reimbursement and compensation claims. In addition, the accident insurance has a pool of preventive information that includes data on the prevention of insured events, the prevention of work-related health hazards, and risks and health hazards for insured persons. This also includes research data on combating occupational diseases.

The umbrella organisation of the accident insurance institutions, the German Association of Occupational Accident Insurance (DGUV), alone has three scientific institutes; the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (IfA), the Institute for Work and Health (IAG) and the Institute for Prevention and Occupational Medicine (IPA). In addition, there are other research institutes at some of the German employer’s liability insurance associations. While the research centres in the area of pension insurance and health insurance process social and health data in order to make it available to science and research, the SGB VII does not provide for the accident insurance data to be systematically made available to other interested parties. Nevertheless, the DGUV also provides data on request. It should be noted that even within one country, the handling of social and health data can be quite different due to legal requirements.

The more countries are included, the more colourful the picture becomes. Even the few examples from Finland, the Netherlands and France show that the task of making datasets available across Europe is a major challenge. Catalogues of datasets whose specifications, standards and formats enable data exchange will have to be created for secondary data use.

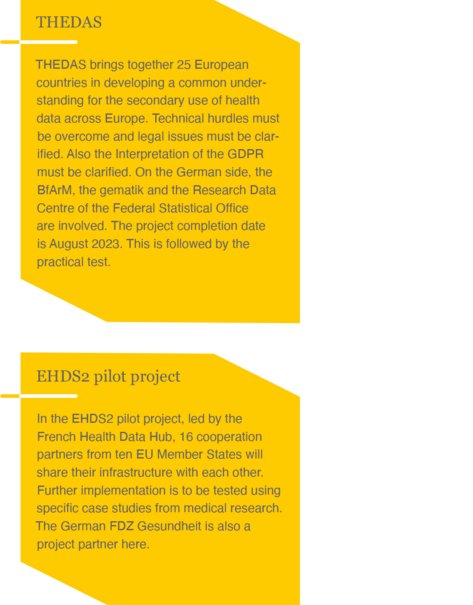

The development of the EHDS for the use of secondary data is likely to be a long process, in which the existing health data in the Member States are successively made accessible across borders. This requires a roadmap that shows how this process can be shaped together, in terms of both content and timing. Cooperation networks such as the Joint Action “Towards the European Health Data Space, THEDAS” should provide assistance.

The diversity of Europe – also with regard to the different data infrastructures and resources – will require a great deal of detailed coordination when setting up the EHDS. The expense is justified by the expected high benefit that large data volumes and high data availability promise.

However, the framework conditions that allow commercial use of health data of the social insurers must be clarified. The actual scope of data for secondary data use will also have to be discussed. In the draft regulation on the EHDS, the European Commission worded maximum ideas that even include administrative data, information on reimbursements and also data from wellness applications. The further legislative process must set limits here. The further design the EHDS should continue to take into account meaningful national differences in the Member States.

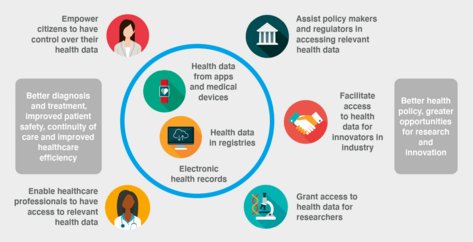

Advantages for the users of the EHDS